Bill Cleveland is one of the founding figures in statistical graphics and data visualization. His two books, The Elements of Graphing Data and Visualizing Data, are classics in the field, still well-worth reading today.

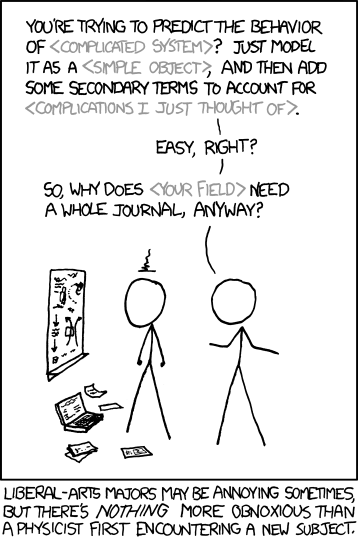

Visualizing is about the use of graphics as a data analysis tool: how to check model fit by plotting residuals and so on. Elements, on the other hand, is about the graphics themselves and how we read them. Cleveland (co)-authored some of the seminal papers on human visual perception, including the often-cited Cleveland & McGill (1984), “Graphical Perception: Theory, Experimentation, and Application to the Development of Graphical Methods.” Plenty of authors doled out common-sense advice about graphics before then, and some even ran controlled experiments (say, comparing bars to pies). But Cleveland and colleagues were so influential because they set up a broader framework that is still experimentally-testable, but that encompasses the older experiments (say, encoding data by position vs length vs angle vs other things—so that bars and pies are special cases). This is just one approach to evaluating graphics, and it has limitations, but it’s better than many competing criteria, and much better than “because I said so” *coughtuftecough* 🙂

In Elements, Cleveland summarizes his experimental research articles and expands on them, adding many helpful examples and summarizing the underlying principles. What cognitive tasks do graph readers perform? How do they relate to what we know about the strengths and weaknesses of the human visual system, from eye to brain? How do we apply this research-based knowledge, so that we encode data in the most effective way? How can we use guides (labels, axes, scales, etc.) to support graph comprehension instead of getting in the way? It’s a lovely mix of theory, experimental evidence, and practical advice including concrete examples.

Now, I’ll admit that (at least in the 1st edition of Elements) the graphics certainly aren’t beautiful: blocky all-caps fonts, black-and-white (not even grayscale), etc. Some data examples seem dated now (Cold War / nuclear winter predictions). The principles aren’t all coherent. Each new graph variant is given a name, leading to a “plot zoo” that the Grammar of Graphics folks would hate. Many examples, written for an audience of practicing scientists, may be too technical for lay readers (for whom I strongly recommend Naomi Robbins’ Creating More Effective Graphs, a friendlier re-packaging of Cleveland).

Nonetheless, I still found Elements a worthwhile read, and it made a big impact on the data visualization course I taught. Although the book is 30 years old, I still found many new-to-me insights, along with historical context for many aspects of R’s base graphics.

[Edit: I’ll post my notes on Visualizing Data separately.]

Below are my notes-to-self, with things-to-follow-up in bold:

Continue reading “The Elements of Graphing Data, William S. Cleveland”