Eighty years ago this week, my grandmother and grandfather were each enthusiastic seven-year-olds, excited for September 1st — their first day of school! At the time, they lived hundreds of kilometers apart and had yet to meet. She had spent her childhood in France but was thrilled to be back in ancestral Poland, in the north-eastern city of Wilejka, where she would finally be able to study in Polish. He was a voracious reader in Poznań, the westernmost large city in Poland at the time. Still, both had laid out their best clothes and filled a satchel with notebooks and pens.

Of course, it was not to be. My grandfather’s mother woke him in the middle of the night and brought him quietly down to the cellar, in the dark, past windows blacked out with curtains and blankets, as German forces began shelling the city. In the morning his apartment still stood, but he saw the broken walls and ruined rooms of the building next door. Meanwhile, my grandmother’s long-awaited Polish school was cancelled as well, eventually replaced by a Russian school as Soviet forces occupied her city.

Somehow, they survived World War II and eventually met as teachers, committed to the critical importance of education in rebuilding their broken country. My grandfather went on to become a professor of history and a leading figure at the University of Zielona Góra, in the city where they finally settled (and where I was born). A few years ago, when he passed away, I found some of the old statistical yearbooks he must have used as research resources.

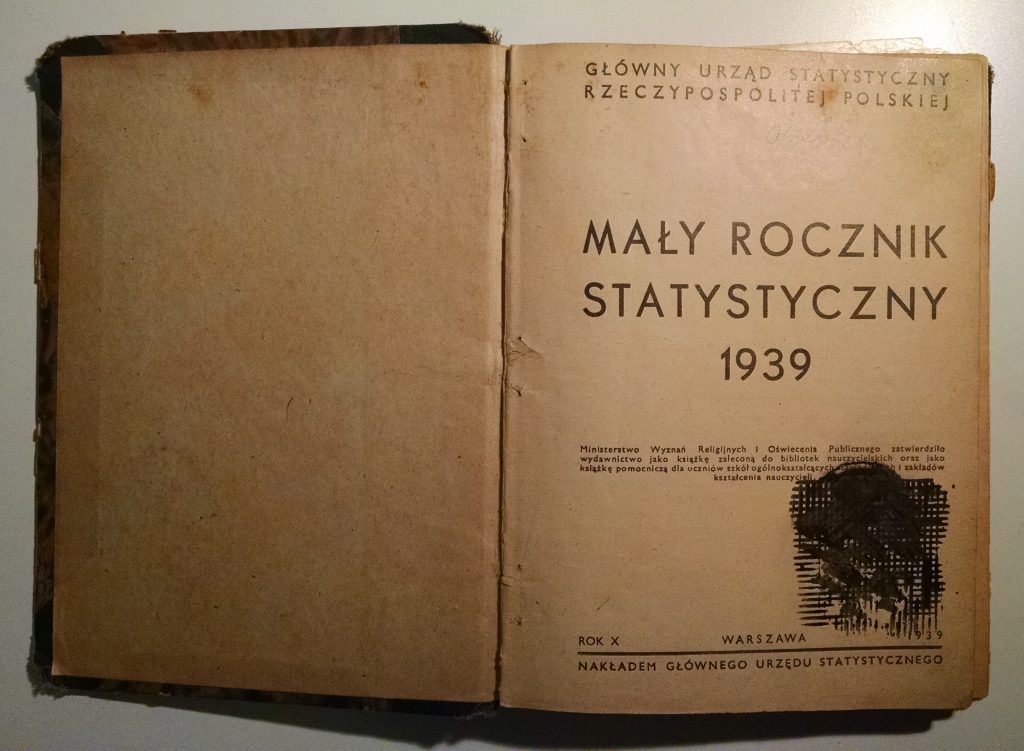

The yearbook from 1939 is particularly touching. As a physical artifact, it has clearly been through a lot: worn from use, spine broken, pages torn, stamped and underlined and scribbled all over.

But it’s the “Foreword to the 10th Edition,” written in April 1939, that really moves me with its premature optimism:

The current edition of the Year-Book closes the first ten years of its existence. Today I can emphatically assert the great utility of this publication … It remains only necessary to express a hope that the Concise Year-Book, completing currently the first decade of its existence and beginning in the near future its second decade… will continually and increasingly fulfill its mission as set out in 1930…

Once again, it was not to be. The statistical service could not continue its planned work, once the war began in September. The Polish government-in-exile in London did manage to publish a Concise Statistical Year-Book for 1939-1941, summarizing what was known about conditions in the German- and Soviet-occupied territories. But the regular annual compilation and publication of Polish statistical yearbooks did not resume until after the war, in 1947 — and even then it was interrupted again during 1951-1955 as the Soviets in charge did not want to risk revealing any state secrets.

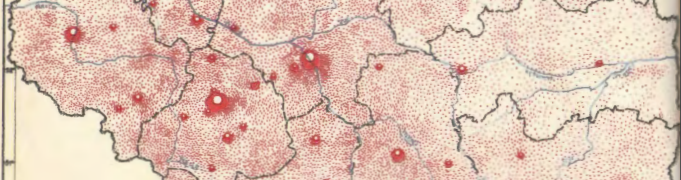

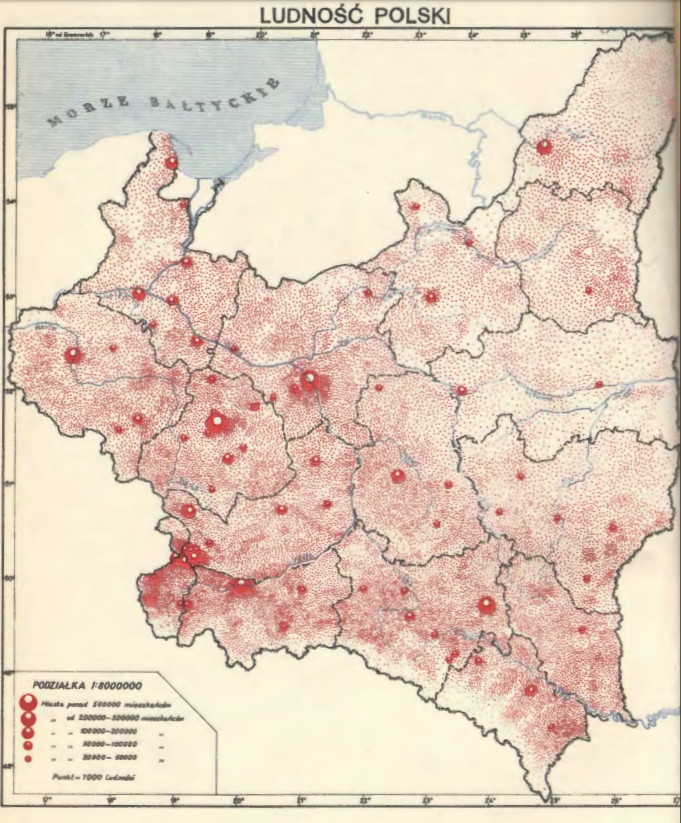

The Polish Wikipedia has a good article on these statistical yearbooks, but unfortunately it’s not yet translated into English. However, you can skim through a scanned PDF of the whole 1939 yearbook. For instance, the lovingly hand-drawn population density map reminds us that there were precursors to the (also beautiful) census dot maps based on 2010 US Census data.

Now, on this 80th anniversary of the war, my own son is eager to start school, while I am preparing to bring the 1939 yearbook to my fall course on surveys and censuses. I am grateful that our life today is so much better than my grandparents’ was, even if it’s hard to be optimistic about the state of the world when you hear the news lately. All we can do is roll up our sleeves and get back to work, trying to leave the place better than we found it.

Another Pole, the poet Wisława Szymborska, said it well:

The End and the Beginning

After every war

someone has to clean up.

Things won’t

straighten themselves up, after all.

Someone has to push the rubble

to the side of the road,

so the corpse-filled wagons

can pass.

Someone has to get mired

in scum and ashes,

sofa springs,

splintered glass,

and bloody rags.

Someone has to drag in a girder

to prop up a wall,

Someone has to glaze a window,

rehang a door.

Photogenic it’s not,

and takes years.

All the cameras have left

for another war.

We’ll need the bridges back,

and new railway stations.

Sleeves will go ragged

from rolling them up.

Someone, broom in hand,

still recalls the way it was.

Someone else listens

and nods with unsevered head.

But already there are those nearby

starting to mill about

who will find it dull.

From out of the bushes

sometimes someone still unearths

rusted-out arguments

and carries them to the garbage pile.

Those who knew

what was going on here

must make way for

those who know little.

And less than little.

And finally as little as nothing.

In the grass that has overgrown

causes and effects,

someone must be stretched out

blade of grass in his mouth

gazing at the clouds.